Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsRethinking the soundness of our debt management: Should we be worried?

History has shown that the financial soundness of emerging markets are particularly vulnerable to external debts, both public and private.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he COVID-19 pandemic has caused great social and economic disruptions with devastating consequences that we had never imagined before. In terms of policymaking, the virus has forced policymakers to override fiscal and monetary orthodoxy in order to save the economy from the brink of calamity. It has been two years, and we still have no clue when this pandemic will end. Fiscal discipline, however, needs to be undertaken to maintain macroeconomic stability, dampen vulnerabilities and improve the overall economic output.

On the one hand, the mounting level of debt caused by the pandemic should be reduced to a safer level in order to avoid more severe crisis and looming inflation. On the other hand, premature withdrawal of the fiscal stimulus to bring down the debt level could risk undermining recovery and cause double-dip recession.

Policymakers are determined to lower the budget deficit to pre-pandemic levels (below 3 percent) by 2023. But is this target realistic? Can we expect a “soft landing”, given the exit strategy policymakers have prepared?

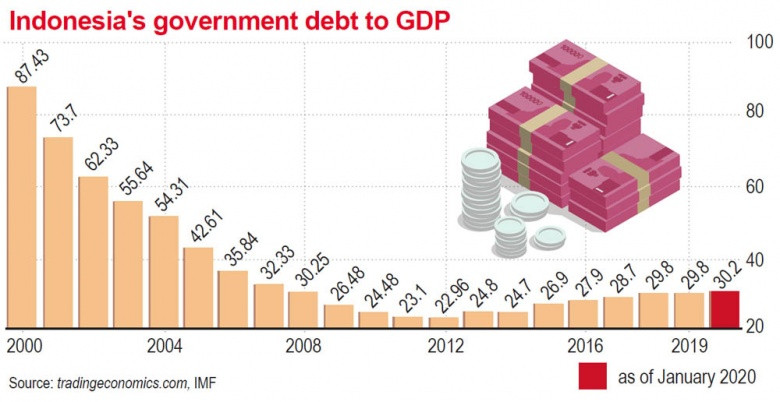

A well-designed exit strategy should take into account sound debt management as a potential solution if policymakers decide to extend fiscal consolidation to keep the expansionary stimulus programs on track. With government debt reaching 40 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) and deficit hovering between 4 and 5 percent, both public and private debts should be reexamined to make sure the payments can be fulfilled. Nonetheless, debt-to-GDP ratio should not be the only metric for assessing risks and vulnerabilities.

The biggest risk Indonesia faces as an emerging market is its current account deficit, which is financed by foreign capital flows to portfolio investment and leads to imbalance in the balance of payments. The imbalance results in capital flows that, when coupled with a lack of foreign direct investment, will result in mounting external debt. External debt exposes a bigger risk than domestic or “official” debt from multilateral institutions and the aid agencies of developed countries, since the creditors, or bondholders, can dump them on a whim, sparking currency depreciation and economic disruption.

Financial fragility as a consequence of overindebtedness in emerging markets, particularly from external debt, can be viewed from three dimensions.

First, countries with adequate foreign reserves or solid fundamentals only suffer very short-lived downturns in capital inflows. Thus, such countries are more resilient during market turmoil and can eventually avoid unexpected financial crisis. Aside from financing external debt payments and imports, foreign reserves can also be a means for central banks to conduct open market operations in order to stabilize financial markets from investor panic.